Born in Mexico City in 1927, painter and draftsman Enrique Chavarría is one of Mexico’s best kept secrets. Late American gallery owner Bryna Prensky said -in a conflicting remark- she held at part responsible for it because, since she met Chavarría in the mid 60’s until she went back to Florida in 1985, she was captivated by his “fabulous technique an immense storehouse of knowledge” and kept all Chavarría’s work for her personal collection1.

Chavarría attended the prestigious art school Academia de San Carlos in Mexico City in the 40’s. Therefore, he received a highly rigorous art education and it is presumed that he might had among his professors, artists Pastor Velázquez – watercolor-, Carlos Alvarado Lang -etching-, Lola Álvarez Bravo -photography- and Carlos Dublan -oil painting-. His known works were produced from 1968 to 1990.

However, after attending art school he led a reclusive life and he did not “work within conventional art structures”2. Furthermore, his surrealistic style reminiscent of Spanish-Mexican artist Remedios Varo, -which at the time was seriously questioned3-, never evolved, all which prevent him from becoming known4 and recognized as part of the Mexican artist scene.

There is no evidence Chavarría attended the “Exposición Internacional del Surrealismo”, the international surrealist exposition held in Mexico City in 1940 at the Galería de Arte Mexicano, nor that he had a close relationship with Remedios Varo which may underpin his allegiance to surrealism and her aesthetical and philosophical ideas. Nonetheless, weather it was a first-hand approach or a bookworm’s one, he certainly shared surrealist’s dreamlike and uncanny imagery along with the fondness for esoteric iconography inspired by astrology, alchemy, Kabbalah and Tarot as a double-folded quest5: to create and to access higher realms of consciousness and existence6.

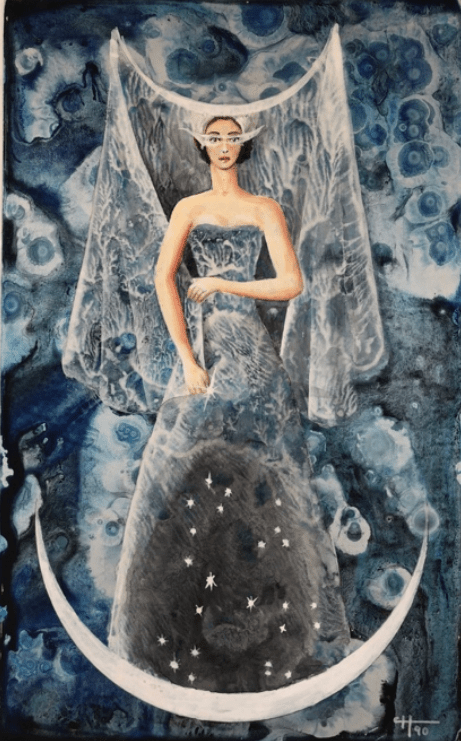

In “Magic Moon”, Enrique Chavarría draws attention to a depiction of what it appears to be an interpretation of “The High Priestess”, card number two in the twenty-two Major Arcana of the Tarot. “Tarot cards have their origin in the hieroglyphic science contained in The Book of Thoth, a form of esoteric knowledge that medieval legend attributed to Abraham […] One major arcana, the High Priestess or Popess, corresponding to number two, depicts the goddess Isis wearing a tiara with the lunar crescent. According the Jesuit Athanasius Kircher, this card contains the key to the sacred alphabets, specifically, the diagram correspondences among the three kingdoms that rule the universe (heaven, earth, hell)” (Battistini, 2007: 2016).

Over a silvered spray-painted background, splatters of blues -French Ultramarine and Pthalo Blue- create a nebulous effect unfolding a cosmic scenery. In the foreground, the painting shows a resemblance of a 40’s paper doll portrait. Facing front, a slender young woman dressed in a strapless evening gown occupies the center of the cosmic space. She exhibits short hair and no jewels, except for a twinkle star bordering her right-hand fingers. Her skin is pinkish and smooth. Tiny nostrils appear above a small but fleshy red mouth. Her dark big eyes are framed in full-arch trimmed line eyebrows. She is staring intense and knowingly at something or someone in front of her, perhaps the viewer.

She is wearing a translucent feather-like mask and a long veil attached to a crescent moon headdress. In symmetry, she is standing at a large white crescent moon in the same way “The High Priestess” from the “Rider Deck” -a Tarot deck collaboration between scholar Arthur Edward Waite and illustrator Pamela Colman in England, 1909-. The mirrored crescent moon asserts her belonging to the moon’s archetypal divine lineage, from the Egyptian goddess Isis to the Christian Virgin Mary. Moreover, the gown’s skirt is covered in little white stars alluding to the starry mantle and probably to the image of Catholic Mexican virgin mother “Our Lady of Guadalupe”.

The face is motionless, the body is rigid, however the portrayal is not lifeless. Life is not exhibited in the human figure but in the objects that cover and surround her, the veil, the mask, the gown and the nebula behind her. The veil and the mask have a velum quality like: membranous. This same nervure pattern covers the midnight blue gown like a white lace. The flimsy and organic textures create a whimsical effect reminiscent to the vegetal, mineral and marine universes.

The rigidness and heaviness of the woman figure and her colossal crown contrast with the fluidity and airiness of her garments and the cosmic scenery suggesting a counterbalance between the solid and the ethereal. The weight of the material against the insubstantiality of the spirit.

The High Priestess is who knows the universe’s secrets. She is the empress of the hidden; is Isis with veil as is featured in Chavarría’s depiction. Bride of the sun represents the yin force, “introspective and receptive” (Reed, 2016: 12). She who holds and protects the sacred, who unlocks the concealed knowledge. Goddess of creativity, intuition and perception. “In a reading for an artist, it means that he gets many of his ideas through intuition” (Gray, 1973: 101). She who has the moon’s gifts at her feet. She who merges the ocean tides and the deep sky. Tamer of the inner and the outer realms.

The Tarot represents the archetypal spiritual journey, “primarily a journey into our own depths. Whatever we encounter along the way is ‘au fond’ an aspect of our own deepest, and highest, self” (Nichols, 1984:1). The Major Arcana represent the qualities we acquire and the experiences and life lessons we must learn in order to achieve spiritual realization depicted in Arcane 21, “The World”. “This can be called the best card in the deck, and when it appears in a Seeker’s layout the Reader can with confidence predict good things of both a material and a spiritual nature (Gray, 1973:142).

What does Chavarría want his “High Priestess” to represent? Why does Chavarría chose “The High Priestess” among the twenty-two Major Arcana? What does she represent for him, his creative quest and/or his vision of the world? How does “Magic Moon” interacts with his other works? What Tarot reading may be posing for Chavarría and/or the viewer?

Finding the narrative thread among Chavarría’s works is a difficult task for several reasons. 1. There is a very limited number of paintings available. 2. He is an unknown artist who has no scholarship. 3. His imagery is cryptic. 4. He is dead and so are his only relatives. 5. His work escapes strict categorization in mainstream movements, styles and chronology.

Nevertheless, he has a very recognizable style, repetitive motifs and patterns, and a coherent visual language that may be approached with the right keys and may reveal an intriguing work worth discovering as Prensky foresaw: “he had remarkable eyes that could see far off places. And he could focus those eyes on both outer reality and that inner reality that becomes known to us through our dreams” (Prensky, ob.cit.).

© Ana Márquez, 2023.

1 His work intrigued me to such degree, that in effect, I became his patron, purchasing every one of the paintings and drawings that I could get from him. This helped him economically but, on the other hand, the result of my keeping him almost all to myself meant that he did not become well known. (Prensky, Enrique Chavarría: Painter of Fantasy and Myth”, 2006).

2 Outsider art is used to describe art that has a naïve quality, often produced by people who have not trained as artists or worked within the conventional structures of art production. “Outsider Art”. (Art term. Tate. http://www.tate.org.uk).

3 Chavarría’s work can be most closely related to that of Remedios Varo, whose mature signature paintings were produced between 1943 and 1963. In contrast, Chavarría’s major works were created between 1968 and 1985, years after Varo’s death and the peak of Surrealism’s popularity in Mexico City. He was definitely exposed to Varo’s works, but his own paintings were seen as copycat or passé by the time they were exhibited in the 1960’s. (Olson, Emily).

4 His work is difficult to identify stylistically and chronologically and because he was socially reclusive, Chavarría’s work has remained largely unknown to most scholars and critics. (Ob.cit.)

5 The allegorical and symbolic images in 14th to 16th-century art, furthermore, were inspired by esoteric contents drawn from Hermeticism, alchemy, and the Kabbalah, closely related disciplines that claimed to fathom the arcane secrets of life by drawing correlations between natural and artistic creation […] Between the 17th and the 19th century, esoteric iconography found a renewed impulse in the illustration of alchemical treatises and in the visionary works of painters such as Fuseli and Blake. It was only in the 20th century, however, that artistic currents such as Surrealism seemed to reconnect their aesthetic and creative principles to past traditions. (Battistini, 2007: 6-7).

6 “Chavarría claimed that his goal in painting was to “sink himself into the universal subconscious in order to become cognizant of a world that is destroying itself and to find himself involved in the miracle of hope … a hope of an encounter with transcendence”. (Cruz, “Homage to the Mexican Painter Enrique Chavarria.” Qtd.in Olson).

Bibliography

Battistini, Matilde. Astrology, Magic, and Alchemy in Art. J. Paul Getty Museum. Los Angeles, 2007.

Cruz, Enrique Ignacio Aguayo . “Homage to the Mexican Painter Enrique Chavarria.” El Sol de Mexico, n.d. in Olson, Emily. “Trascending ‘Insider’ art: Enrique Chavarría, Surrealism, and Outsider art. Texas Christian University, 2011.

Enrique Chavarría: Surrealism and the Fantastic. (exhib. catalog). Tallahassee, Florida: The Mary Brogan Museum of Art and Science, 2006.

“Giant Rider-Waite Tarot Deck”. U.S. Games Systems, Inc. Stamford, 2010.

Grey, Eden. Mastering the Tarot. New American Library. New York, 1973.

Nichols, Sallie. Jung and Tarot: An Archetypal Journey. Weiser Books. San Francisco, 1984.

Olson, Emily. “Trascending ‘Insider’ art: Enrique Chavarría, Surrealism, and Outsider art. Texas Christian University, 2011.

“Outsider Art”. Art terms. Tate. http://www.tate.org.uk

Prensky, Bryna. “Enrique Chavarría: Painter of Fantasy and Myth,” in Enrique Chavarría: Surrealism and the Fantastic. (exhib. catalog) Tallahassee, Florida: The Mary Brogan Museum of Art and Science, 2006.

Reed, Theresa. The Tarot Coloring Book. Sounds True. Boulder, 2016.